“I’m fortunate enough to be able to open a legal distillery and not have to worry about getting in trouble,” said Brian Call.

Call, a seventh-generation moonshiner, was born and raised in Wilkes County, North Carolina. He learned the art of distilling clear liquor from corn from his father, who learned it from his father, who learned it from his father, and so on and so forth back to the early 1800s. Of course for most of those years that distilling happened in secret, the Call family making and distributing the whiskey below the radar, tucked away in the woods to avoid being caught by law enforcement.

It’s been about a year since Call Family Distillers opened for business right next to Lowe’s Park at Rivers Edge in Wilkesboro, all above board and perfectly legal. Four flavors–clear, cherry, strawberry and apple pie–are available for purchase in mason jars or for tasting, either straight or mixed into cocktails. The apple pie recently received a gold medal from the American Distiller Institute for best moonshine flavor, and the stuff is available in ABC stores all over North Carolina. Call said the process of making the moonshine hasn’t changed much, except for one major difference.

“It’s a whole lot cleaner now,” he said with a twang and a chuckle. “Everything’s food grade now, the building is a lot cleaner than bein’ out in the woods makin’ moonshine. Back then you could walk in and find a possum in your mash or something’, but we don’t have to worry about that now.”

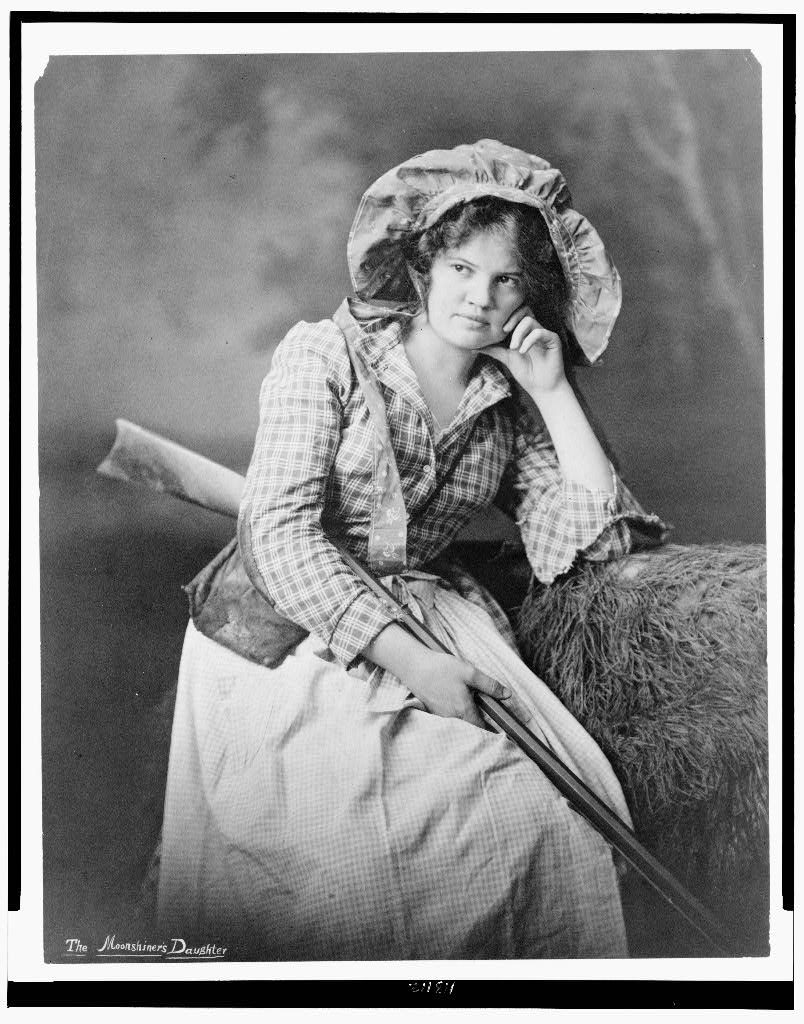

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

There is, of course, another major difference–Call doesn’t have to worry about the feds coming after him and throwing him in jail.

For the Call family, it all started with the Reverend Daniel Call back in the mid 19th century. The Reverend moved to Lynchburg, Tennessee, where he opened a merchant store and led a congregation. When he wasn’t delivering sermons at church or running the shop he was out back making whiskey, and legend has it that in the 1860s he began mentoring a young man and teaching him how to distill from start to finish, and the two of them started a small business selling the liquor together. It wasn’t long before members of Call’s congregation caught wind of his side business and gave him an ultimatum: it was either the church or the whiskey. He chose the church and sold off his portion of the distillery to his partner, Jasper “Jack” Newton Daniel. Perhaps you’ve heard of him? (A June 2016 New York Times article revealed that Jack Daniel’s recently released a new piece of information about its inception and has been gradually incorporating the plot twist into its story and distillery tours–it was actually Call’s slave, Nearis Green, who taught the young Jack Daniel how to make whiskey.)

Ever since then, generation after generation of the Call family (and hundreds of Appalachian families like them) continued down the lucrative and often tumultuous road of making moonshine (also known as white lightning, white whiskey, hooch, mountain dew and homebrew).

“Years ago there wasn’t a whole lot of jobs in this area,” Call said. “But people would make whiskey and support their families pretty good. My dad and my grandpa, they’d grow their corn in the summertime and make whiskey in the wintertime.”

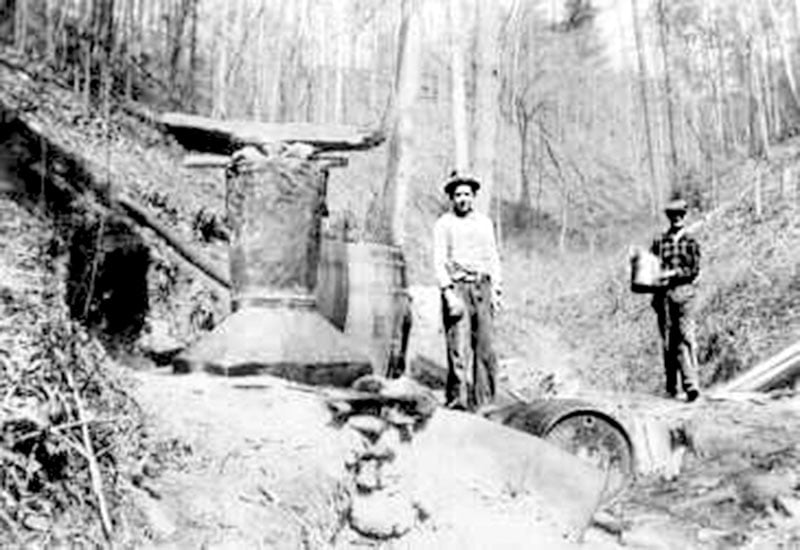

A still in Tellico, Tennessee. Image courtesy of moonshiner28.com.

Moonshining families like the Calls made it in their their barns, on their farms, tucked away in the woods, but unlike the homebrewers of today who tinker with the beer-making kits they got as a graduation gift in their kitchens to fill their own fridges, it wasn’t just a hobby–it was their livelihood.

“Historically, the distillation of moonshine was essential for poor Appalachian farmers as a way of earning an income by converting poor quality corn into alcohol,” said Jane Peyton, drinks educator and author of School of Booze: An Insider’s Guide to Libations, Tipples and Brews. “These farmers were independent and hardy people who did not welcome intrusion from outsiders, so when the post-revolutionary government levied taxes on distilled spirits as a way to raise funds, they were resentful and angry and refused to pay the taxes.”

Distilling continued all over the region, but the process became more secretive as the farmers kept it outside the law, and thus was born a now centuries-old association of moonshine with outlaws. Even so, for a lot of moonshiners, it was so ingrained into their lives that it didn’t feel like they were doing anything wrong.

“In my family, my dad taught me how to do everything, and his daddy taught him, and it’s just been a family affair over the years,” Call said. “My dad was able to do it without gettin’ into trouble and he couldn’t get enough of it. It just came naturally. We just thought it wasn’t no big deal, you know, never worried about nothin’.”

Even being arrested on conspiracy and thrown in prison for a few years couldn’t keep Call’s father away from the stills. Call Sr. was arrested after “somebody rolled over on him,” and he did time in prison on the Donaldson Air Force base in South Carolina. Not only did it not slow him down, but the stint behind bars stoked his business.

“That was where a lot of the moonshiners went, and a lot of ‘em picked up new customers,” Call laughed. “He said he found his best customers when he was in prison.”

And the advice his dad gave him about how to stay in the game without getting caught?

Image courtesy of moonshiner28.com.

“He said to just deal with the right people, run it like a business and have people in place you can trust,” Call said.

Call is deliberate in pointing out that his dad’s arrest was the result of someone narc-ing on him, and that he was never actually caught in action. And there was most definitely action.

When Call’s father wasn’t manning the stills, he was flying down gravel mountain roads in a 1961 New Yorker–which is on display at the distillery–loaded down with jugs of moonshine. There was more to the business than mashing, fermenting and distilling–once the hooch ran off clear, someone had to get it from point A to point B. Which is where the souped up cars you may recognize today came in.

An abandoned still in Clay County, Fla. Image courtesy of Clay County Historical Archives.